The Common after the Second World War

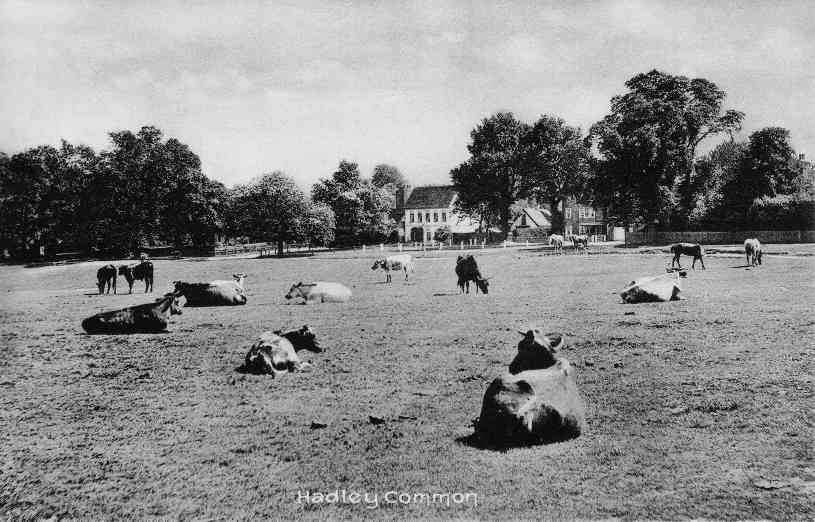

Grazing on the Common steadily declined from the mid 19th century onwards as more and more farmland was developed for housing, a decline which accelerated when motor vehicles started to replace horse drawn ones from the early 20th century onwards, and grazing would seem to have ceased completely by the 1950s. From that point onwards the Churchwardens had neither the time nor the money for the upkeep, and the Common fell into rather a state of disrepair, which continued until it eventually came under new management in 1981 (see below).

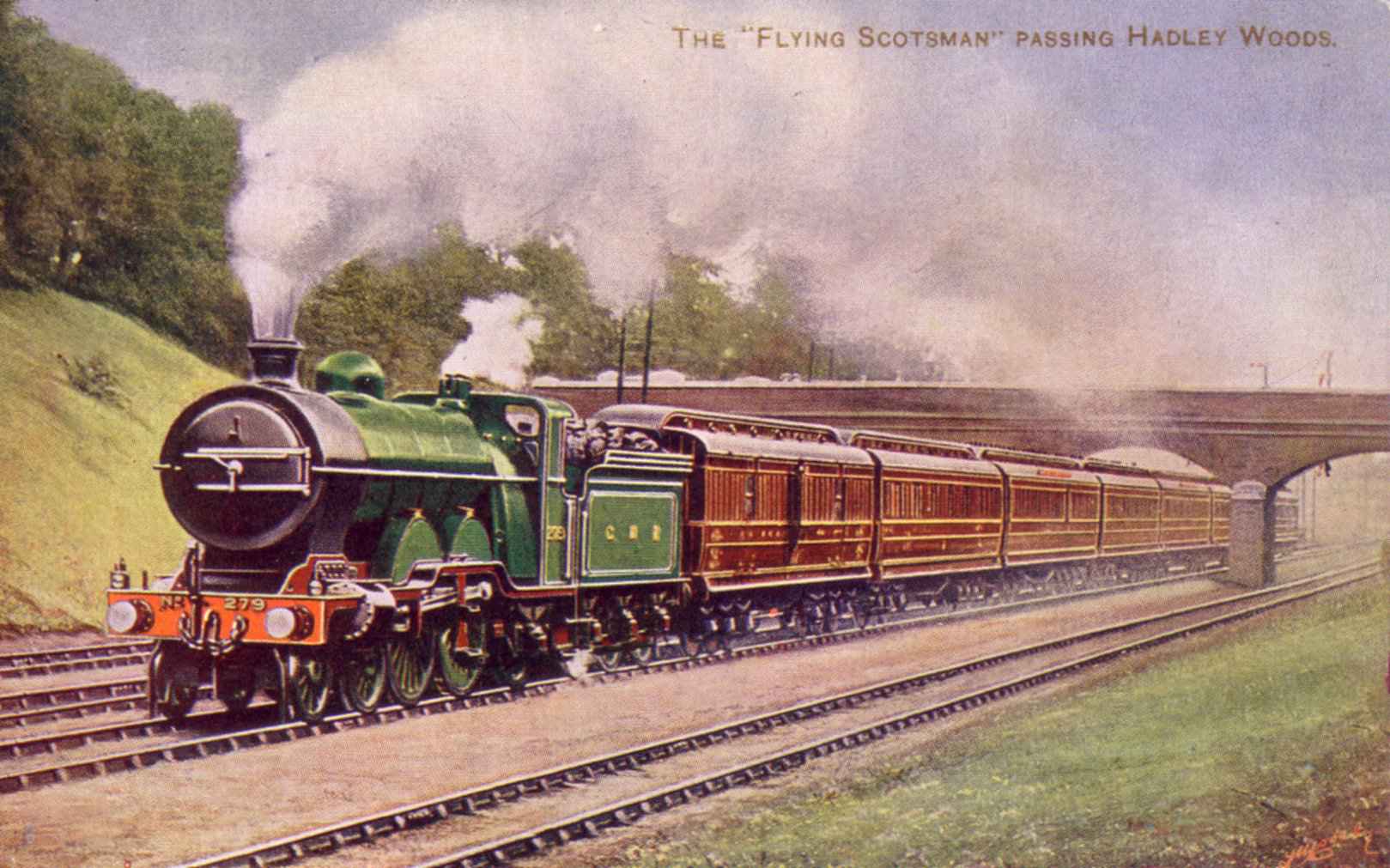

By 1970 most of the Common had been registered as common land under the Commons Registration Act 1965 (the register is now held by Barnet Council). Several small areas which had been leased by the Churchwardens were (correctly) omitted from the register plan, together with other small areas around the periphery, which – it is now clear – should really have been registered. In addition to this, three areas of land were included in the register when they should clearly not have been; two of these are very small, but the third was an egregious mistake in that all the land within the railway security fence was registered as common land (the Trust is not affected by this, though, because it does not own any of the three areas concerned). For these and other reasons the boundary of the registered common land and the legal boundary of the Common are not contiguous over substantial parts of their lengths.

In 1981 new Rules and Orders were formed which placed the management of the Common in the hands of a Management Committee appointed by the Commoners at their Annual General Meetings, together with two Curators appointed annually by the Committee; additionally the Committee was advised by the legally qualified Clerk to the Churchwardens who also acted as its Secretary. The Committee was to meet not less than three times a year to receive from the Curators a report on their management of the Common since its last meeting, and to give to the Curators “such directions with regard to the management of the Common as it thought proper”. At each Annual General meeting the Curators were also to submit a printed account, duly audited, of all moneys received and expended by them during the previous year. Though there was no specific provisions in the Rules and Orders for this, the Committee appointed from amongst itself a financially qualified Treasurer, and (although in practice this varied from the provisions laid down in the Rules and Orders) all monies and investments were held in the name of the Churchwardens as trustees of the Common.

Under the terms of the 1777 Act, a number of leases of parts of the Common had been granted prior to 1981, and the Committee was empowered to renew any of them for terms not exceeding 21 years. The Committee was also empowered to “grant license and permission to the owner or occupier of any lands bordering upon or adjoining to the common to have, make and use any gates, ways or passages over the Common, which may be convenient although not necessary, to lead to any house or outhouse or lands of such owner or occupier, provided always that an annual rent be reserved for such license, and that the term thereof shall not exceed 21 years” (this wording closely reflects that of the 1777 Act itself). Such easements and leases were to be “by an instrument in writing and where necessary or appropriate under seal expressed to be made by the Churchwardens of the Parish of Monken Hadley as trustees of the Common by the direction of the Management Committee but so drawn as to impose no personal liability on the Churchwardens or either of them”. (Under the terms of the 2022 Act all the existing leases were transferred from the Churchwardens to the Trust.)